PART.2

ARC 100 : Introduction à l’Archéologie / Introduction to Archaeology

Bone wasting reveals the owner of this medieval skull to have suffered from leprosy. An unhealed gash on the forehead suggests that the leper warrior died a violent death, perhaps in battle. Credit: Mauro Rubini

Isotope Geochemistry

Bones can tell much about the lives of past humans when archaeologists apply the right chemical analysis. The ratio of isotopes — different versions of elements such as nitrogen and carbon — can reveal the diets of ancient peoples. But such chemical balances can also provide unique markers that reveal where a person grew up.

"When you're raised on a piece of land, you absorb the chemical signatures of where you were raised from groundwater and plants that grew in the soil," saihttp://cms.technewsdaily.com/administrator/index.php?option=com_content§ionid=-1&task=edit&cid[]=2810d David Hurst Thomas, a curator in anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

That means the level of a certain strontium isotope can tell archaeologists about whether humans buried at Spanish missions were born in Florida or in Spain. Similarly, archaeologists found soldiers from places as diverse as Finland and Scotland who ended up buried in the same German mass grave dating back to 1636, after they presumably died at the Battle of Wittstock during the Thirty Years' War.

Toni Massey (Archaeos) and Jennifer McKinnon (Flinders University) undertaking magnetometer survey at Anuru Bay. Credit: Australian National University.

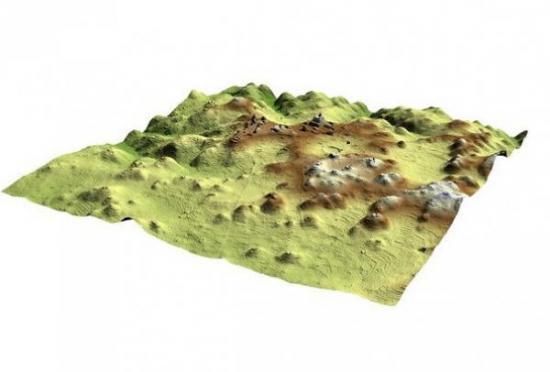

Radar, Magnetometers & Soil Resistivity Tests

Before excavation begins, archaeologists can get a peek beneath the surface with a wide array of technologies. Such instruments create a 3-D image of what lies beneath and give archaeologists a huge edge in knowing where to dig without bringing in a backhoe to tear up everything.

Ground-penetrating radar transmits pulses into the ground that reflect off buried materials, buildings and soil changes. Magnetometers detect buried artifacts based on the changes they create in the Earth's magnetic field. And soil resistivity instruments can pick up on similar buried features based on abrupt changes in electric current as it runs through the soil moisture.

Occasionally, the magnetometer or another instrument may detect an artifact or building that almost seems like a ghost signal, because archaeologists fail to find it despite digging. That points to the limits of human perception in following up on the technological leads, said David Hurst Thomas, a curator in anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

"If we open up the site and decide to excavate, sometimes the instruments see things that we can't see as archaeologists," Thomas said.

Satellite images have revealed hidden streets and buildings at Egyptian sites such as Tanis. Credit: University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Satellite Imaging from Space

Nobody from Indiana Jones' day could have imagined satellites high above the Earth helping archaeologists pinpoint the locations of buried ruins. But now, archaeologists regularly look to the visual images compiled by Google Earth to scan for their next big dig, and use radar imagery from NASA or commercial satellites to unearth hidden treasures.

Infrared satellite images have revealed pyramids, streets and palaces that lie buried in Egypt, as well as ancient rivers hidden beneath the Sahara. Such radar imagery has steadily improved over the years until it can now resolve buried features as small as 1.3 feet (0.4 meters), and as deep as 33 feet (10 meters), said Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham.

Archaeologists may even someday face a time when remote-sensing technology can create detailed images of even the smallest buried objects. That could create a mild professional dilemma.

"What happens when satellite radar images have a resolution of a couple inches, and can go deeper?" Parcak said. "Will we ever have to stop digging? I hope not."

A color LiDAR image of the Maya landscape shows the density of terracing in the ancient city of Caracol. Credit: Caracol Archaeological Project.

LIDAR

Above the jungles of Central America, a device aboard an aircraft used millions of laser pulses to penetrate the thick forest canopy and map ancient Mayan settlements in 3-D. That demonstrated the power of LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), a technology that has transformed archaeology over the past five years.

LIDAR's ability to image everything down to 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) means that archaeologists can create detailed reconstructions of everything from the siege works outside old U.S. forts to underground tunnels from World War I in France.

Thirty years ago, using photographs and plain old pen and pencil to survey would take weeks," said Tony Pollard, director of the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. "Now, LIDAR can do it in minutes."

The technology can even measure subtle differences in crop height that may reveal buried features in everything from ditches to buildings, said Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. She added that using such 3-D mapping power with satellite imaging could give archaeologists a powerful combination of tools for the future.

Robot explorers

A snake robot could soon help archaeologists explore man-made caves in Egypt that are too dangerous for humans. Credit: Howie Choset, Carnegie Mellon University

Indiana Jones may wish he had a robot that could have endured the dangers he faced over his fictional career. Modern archaeologists have increasingly deployed such robotic explorers to check out ancient Roman shipwrecks beneath the Mediterranean waves, or to crawl into claustrophobic shafts leading deep into the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.

The uncomplaining nature of robots that can go where no human has gone before makes them ideal for scoping out virtually inaccessible archaeological sites. That has mostly meant underwater archaeology so far, with the notable exception of the Djedi Project robot helping archaeologists in Egypt. In another case, a team needed a submersible robot to investigate a World War I underground headquarters in Belgium that had flooded.

"We actually used a remote vehicle which would normally be used on oil platforms," said Tony Pollard, director of the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Archaeologists can expect smarter and even more flexible robotic assistants in the future. Carnegie Mellon University is developing a snake robot that can wriggle into man-made caves containing ancient ship pieces in Hurghada, Egypt.

Sorry it had to be snakes, Indiana Jones.