INSTITUT SUPERIEUR D'ANTHROPOLOGIE

INSTITUT OF ANTHROPOLOGY

COURS ONLINE – COURS A DISTANCE

INSCRIPTIONS : SEPTEMBRE 2024

REGISTER NOW

ESPAGNE –

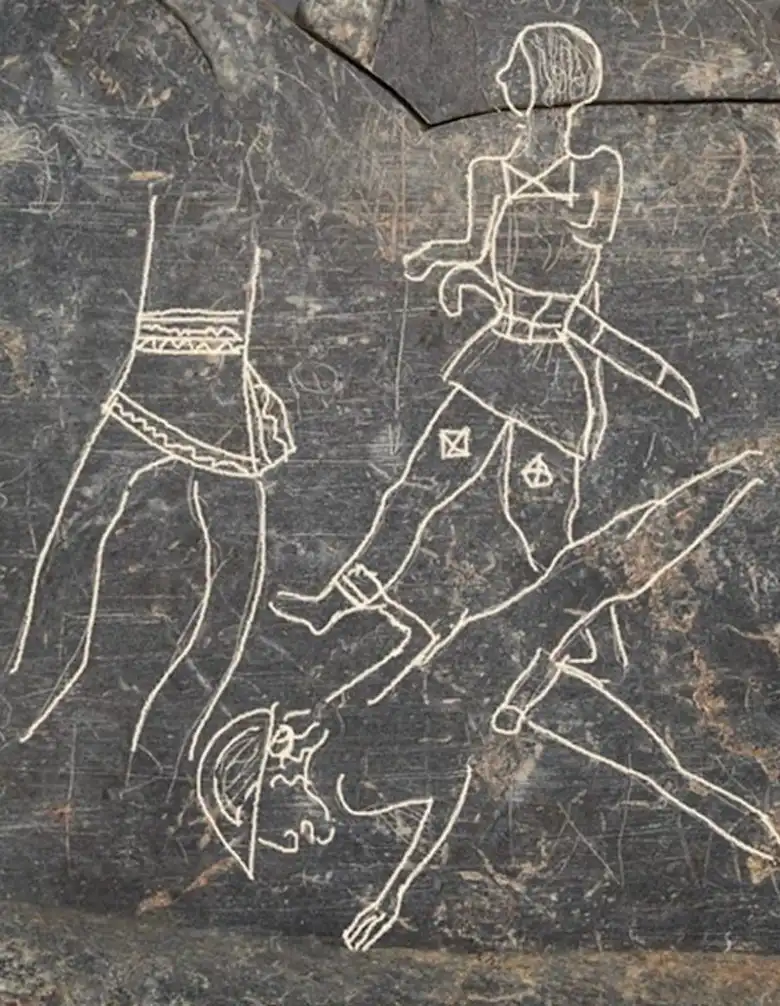

Casas del Turunuelo - Archaeologists representing Spain’s National Research Council (CSIC) excavating at the archaeological site of Casas del Turunuelo have uncovered a slate plaque about 20 centimeters engraved on both sides where various motifs can be identified. The slate plaque includes drawing exercises, a battle scene involving three characters, and repeated depictions of faces or geometric figures. According to early indications, this rare find in Guareña (Badajoz, Spain) may have supported the engraver as they carved designs into pieces of wood, ivory, or gold. The new campaign has also made it possible to discover the location of the east door that gives access to the Stepped Room, excavated in 2023 and known for the discovery of the first figured reliefs of Tartessos. The Tartessians, who are thought to have lived in southern Iberia (modern-day Andalusia and Extremadura), are regarded as one of the earliest Western European civilizations. The Late Bronze Age saw the emergence of the Tartessos culture in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula in Spain. The culture is characterized by the use of the now-extinct Tartessian language, which is combined with local Phoenician and Paleo-Hispanic characteristics. The Tartessos people were skilled in metallurgy and metalworking, creating ornate objects and decorative items. At a press conference, the team of CSIC experts highlighted the importance of the discovered slate plaque, which shows four individuals identified as warriors, given their decorated clothing and the weapons they carry. Initial indications, though they require further investigation, point to the piece being a jeweler’s slate, a material that would have supported the artist while they engraved the motifs on pieces of wood, ivory, or gold. The researchers also worked on the eastern gate, which they identified in 2023. Based on the nature of the documented architectural remains and the discovery of the building’s east door in the center of a monumental facade more than three meters high, the research team believes that this door confirms the main access to the building on its eastern end, which retains its two constructive floors. The door links the Stepped Room to a large slate-paved courtyard, which has a cobblestone corridor in front of it. This corridor separates the main body of the building from a set of rooms where interesting material lots have been recovered.

Casas del Turunuelo - Archaeologists representing Spain’s National Research Council (CSIC) excavating at the archaeological site of Casas del Turunuelo have uncovered a slate plaque about 20 centimeters engraved on both sides where various motifs can be identified. The slate plaque includes drawing exercises, a battle scene involving three characters, and repeated depictions of faces or geometric figures. According to early indications, this rare find in Guareña (Badajoz, Spain) may have supported the engraver as they carved designs into pieces of wood, ivory, or gold. The new campaign has also made it possible to discover the location of the east door that gives access to the Stepped Room, excavated in 2023 and known for the discovery of the first figured reliefs of Tartessos. The Tartessians, who are thought to have lived in southern Iberia (modern-day Andalusia and Extremadura), are regarded as one of the earliest Western European civilizations. The Late Bronze Age saw the emergence of the Tartessos culture in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula in Spain. The culture is characterized by the use of the now-extinct Tartessian language, which is combined with local Phoenician and Paleo-Hispanic characteristics. The Tartessos people were skilled in metallurgy and metalworking, creating ornate objects and decorative items. At a press conference, the team of CSIC experts highlighted the importance of the discovered slate plaque, which shows four individuals identified as warriors, given their decorated clothing and the weapons they carry. Initial indications, though they require further investigation, point to the piece being a jeweler’s slate, a material that would have supported the artist while they engraved the motifs on pieces of wood, ivory, or gold. The researchers also worked on the eastern gate, which they identified in 2023. Based on the nature of the documented architectural remains and the discovery of the building’s east door in the center of a monumental facade more than three meters high, the research team believes that this door confirms the main access to the building on its eastern end, which retains its two constructive floors. The door links the Stepped Room to a large slate-paved courtyard, which has a cobblestone corridor in front of it. This corridor separates the main body of the building from a set of rooms where interesting material lots have been recovered.

Scenes of Warriors from 6th Century BC on a Slate Plaque Discovered at Tartessian Site in Spain - Arkeonews

COLOMBIE / VENEZUELA –  Orenoque - Researchers made a groundbreaking discovery of what is thought to be the world’s largest prehistoric rock art. Enormous engraved rock art of anacondas, rodents, giant Amazonian centipedes, and other animals along the Orinoco River in Colombia and Venezuela may have been used to mark territory 2,000 years ago. Rock engravings recorded by researchers from Bournemouth University (UK), University College London (UK) and Universidad de los Andes (Colombia), believe this is the largest single rock engraving recorded anywhere in the world. Some of the engravings are tens of meters long – with the largest measuring more than 40m in length. While some of the locations were previously known, the team has used drone photography to map 14 sites of monumental rock engravings, which are defined as those that are more than four meters wide or high, and has also found several more. While it is difficult to date rock engravings, similar motifs used on pottery found in the area indicate that they were created anywhere up to 2,000 years ago, although possibly much older. Many of the largest engravings are of snakes, believed to be boa constrictors or anacondas, which played an important role in the myths and beliefs of the local Indigenous population. vvTheir size makes them visible from a distance, suggesting they were used as ancient signposts that told travelers along the prehistoric trade route whose territory they were entering and leaving. The new findings were published on Monday in Antiquity. The engravings may represent mythological traditions that continue today, says archaeologist and anthropologist Carlos Castaño-Uribe, scientific director of the Caribbean Environmental Heritage Foundation in Colombia. The researchers located 157 rock art locations between the upriver Maipures Rapids and the downstream Colombian city of Puerto Carreño. Of these, more than a dozen had engravings longer than four meters (about 13 feet). The largest is the anaconda, which is over 40 meters (roughly 130 feet) in length. Riris says it is likely the largest known prehistoric rock engraving in the world.

Orenoque - Researchers made a groundbreaking discovery of what is thought to be the world’s largest prehistoric rock art. Enormous engraved rock art of anacondas, rodents, giant Amazonian centipedes, and other animals along the Orinoco River in Colombia and Venezuela may have been used to mark territory 2,000 years ago. Rock engravings recorded by researchers from Bournemouth University (UK), University College London (UK) and Universidad de los Andes (Colombia), believe this is the largest single rock engraving recorded anywhere in the world. Some of the engravings are tens of meters long – with the largest measuring more than 40m in length. While some of the locations were previously known, the team has used drone photography to map 14 sites of monumental rock engravings, which are defined as those that are more than four meters wide or high, and has also found several more. While it is difficult to date rock engravings, similar motifs used on pottery found in the area indicate that they were created anywhere up to 2,000 years ago, although possibly much older. Many of the largest engravings are of snakes, believed to be boa constrictors or anacondas, which played an important role in the myths and beliefs of the local Indigenous population. vvTheir size makes them visible from a distance, suggesting they were used as ancient signposts that told travelers along the prehistoric trade route whose territory they were entering and leaving. The new findings were published on Monday in Antiquity. The engravings may represent mythological traditions that continue today, says archaeologist and anthropologist Carlos Castaño-Uribe, scientific director of the Caribbean Environmental Heritage Foundation in Colombia. The researchers located 157 rock art locations between the upriver Maipures Rapids and the downstream Colombian city of Puerto Carreño. Of these, more than a dozen had engravings longer than four meters (about 13 feet). The largest is the anaconda, which is over 40 meters (roughly 130 feet) in length. Riris says it is likely the largest known prehistoric rock engraving in the world.

Giant Prehistoric Rock Engravings Discovered in South America May Be The World’s Largest - Arkeonews

ALLEMAGNE –  Reutlingen - Archaeologists found a collection of medieval game pieces at a forgotten castle in southern Germany. Among the discoveries are a well-preserved chessman, gaming pieces, and dice, dating from the 11th to 12th centuries AD. An excellently preserved knight piece was discovered during archaeological excavations at a forgotten castle in southern Germany. The find is part of a unique games collection, which also includes other gaming pieces and dice. The discoveries were made at an unknown castle in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg’s Reutlingen district during excavations In addition to the chess piece, four flower-shaped game pieces were found, as well as a dice with six eyes. They were carved from antlers. The eyes and mane of the 4 cm high horse figure are vividly shaped. This elaborate design is typical of particularly high-quality chess pieces from this period. The red paint residues found on the flower-shaped pieces are currently being chemically analyzed.

Reutlingen - Archaeologists found a collection of medieval game pieces at a forgotten castle in southern Germany. Among the discoveries are a well-preserved chessman, gaming pieces, and dice, dating from the 11th to 12th centuries AD. An excellently preserved knight piece was discovered during archaeological excavations at a forgotten castle in southern Germany. The find is part of a unique games collection, which also includes other gaming pieces and dice. The discoveries were made at an unknown castle in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg’s Reutlingen district during excavations In addition to the chess piece, four flower-shaped game pieces were found, as well as a dice with six eyes. They were carved from antlers. The eyes and mane of the 4 cm high horse figure are vividly shaped. This elaborate design is typical of particularly high-quality chess pieces from this period. The red paint residues found on the flower-shaped pieces are currently being chemically analyzed.

Archaeologists Unearthed a 1000-year-old Medieval Game Collection in a Castle in Southern Germany - Arkeonews

ARMENIE -

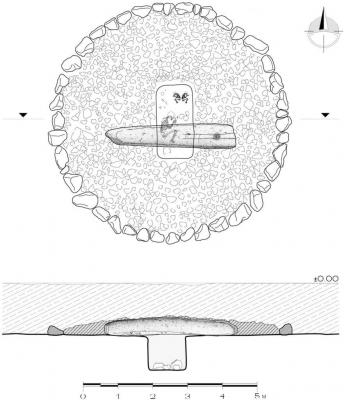

Lchashen - An international team of researchers has unearthed the remains of an adult woman and two infants buried under a basalt monument known as a dragon stone at the Lchashen site in Armenia. The dragon stones, “serpent-stones” or Vishapakar are prehistoric basalt stelae carved with animal images, predominantly found in Armenia and its surroundings. Their name derives from old Armenian folklore and no one really knows why exactly they are called the Dragon Stones. Approximately 150 have been documented. More than ninety in the Republic of Armenia, the remaining ones in adjacent areas. They range in height from about 150 to 550 cm. Archaeologists have identified three types of dragon stones: those with carvings resembling fish (piscis); those that resemble the remains of bovids, such as goats, sheep, cows, and so forth (vellus); and hybrid dragon stones, which combine the two types. The discovery in Lchashen offers a new perspective, as the three-and-a-half meter tall stele with the image of a sacrificed ox ( vellus type ) was found over a burial dating from the 16th century BC. One of the most significant archaeological sites in Armenia, Lchashen is well-known for its profusion of Bronze Age artifacts. This site’s excavations have uncovered many artifacts, including intricate funerary structures, metal tools, and pottery. That is, however, the first instance of a burial being discovered in close proximity to a dragon stone, which is uncommon given the regional funerary contexts. This link between the interment of infants and a highly esteeme d monument raises the possibility of a ritual or symbolic significance that is currently unclear. The stone was discovered in 1980. After initial examination of the stone in situ, it and other materials excavated from the burial site were transported to the Metsamor Historical-Archaeological Museum-Reserve. It contained artifacts, animal bones, and the remains of a human skeleton (believed to be that of an adult woman). Unfortunately, the woman’s bones are now missing. They were reportedly sent to Russia in the 1980s for further examination and have not been found since. But the bones of the two infants, known as Dragon1 and Dragon2, remain. They were not even mentioned in the initial publications about this barrow.The two babies, who were between the ages of 0 and 2 months, had well-preserved remains. Ancient DNA analyses on these remains showed that they were second-degree relatives with identical mitochondrial sequences, indicating a close relationship. These people’s genetic ancestry profiles also revealed commonalities with other Bronze Age people from the area, offering important insights into the genetic makeup of prehistoric populations in the Caucasus. This discovery has multiple implications. First, the connection between the burials and the dragon stones raises the possibility that these monuments served a purpose other than decoration or remembrance, such as ritual or funerary. As the researchers explain: “The event envisaged by the burial is in any case exceptional, both from the point of view of genetics and from the archaeological viewpoint. In Late Bronze Age Armenia in general and at Lchashen in particular, burials of children are rare and the burial of two newborns combined with a monumental stela is unique.”Stelae were sometimes used to mark graves in the South Caucasus, but none of the 454 Bronze Age graves excavated at Lchashen were marked by any type of stele, the researchers wrote in their paper. Only this grave was marked with a dragon stone. The presence of infant remains under such a monolith also raises questions about the funerary practices and beliefs related to death and the afterlife in Bronze Age society in Armenia. The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Lchashen - An international team of researchers has unearthed the remains of an adult woman and two infants buried under a basalt monument known as a dragon stone at the Lchashen site in Armenia. The dragon stones, “serpent-stones” or Vishapakar are prehistoric basalt stelae carved with animal images, predominantly found in Armenia and its surroundings. Their name derives from old Armenian folklore and no one really knows why exactly they are called the Dragon Stones. Approximately 150 have been documented. More than ninety in the Republic of Armenia, the remaining ones in adjacent areas. They range in height from about 150 to 550 cm. Archaeologists have identified three types of dragon stones: those with carvings resembling fish (piscis); those that resemble the remains of bovids, such as goats, sheep, cows, and so forth (vellus); and hybrid dragon stones, which combine the two types. The discovery in Lchashen offers a new perspective, as the three-and-a-half meter tall stele with the image of a sacrificed ox ( vellus type ) was found over a burial dating from the 16th century BC. One of the most significant archaeological sites in Armenia, Lchashen is well-known for its profusion of Bronze Age artifacts. This site’s excavations have uncovered many artifacts, including intricate funerary structures, metal tools, and pottery. That is, however, the first instance of a burial being discovered in close proximity to a dragon stone, which is uncommon given the regional funerary contexts. This link between the interment of infants and a highly esteeme d monument raises the possibility of a ritual or symbolic significance that is currently unclear. The stone was discovered in 1980. After initial examination of the stone in situ, it and other materials excavated from the burial site were transported to the Metsamor Historical-Archaeological Museum-Reserve. It contained artifacts, animal bones, and the remains of a human skeleton (believed to be that of an adult woman). Unfortunately, the woman’s bones are now missing. They were reportedly sent to Russia in the 1980s for further examination and have not been found since. But the bones of the two infants, known as Dragon1 and Dragon2, remain. They were not even mentioned in the initial publications about this barrow.The two babies, who were between the ages of 0 and 2 months, had well-preserved remains. Ancient DNA analyses on these remains showed that they were second-degree relatives with identical mitochondrial sequences, indicating a close relationship. These people’s genetic ancestry profiles also revealed commonalities with other Bronze Age people from the area, offering important insights into the genetic makeup of prehistoric populations in the Caucasus. This discovery has multiple implications. First, the connection between the burials and the dragon stones raises the possibility that these monuments served a purpose other than decoration or remembrance, such as ritual or funerary. As the researchers explain: “The event envisaged by the burial is in any case exceptional, both from the point of view of genetics and from the archaeological viewpoint. In Late Bronze Age Armenia in general and at Lchashen in particular, burials of children are rare and the burial of two newborns combined with a monumental stela is unique.”Stelae were sometimes used to mark graves in the South Caucasus, but none of the 454 Bronze Age graves excavated at Lchashen were marked by any type of stele, the researchers wrote in their paper. Only this grave was marked with a dragon stone. The presence of infant remains under such a monolith also raises questions about the funerary practices and beliefs related to death and the afterlife in Bronze Age society in Armenia. The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Two Infant burials found under prehistoric “Dragon Stone” in Armenia - Arkeonews