ANCIENT TEXTILES OF PERU

Paul Goulder

Source - http://www.peruviantimes.com/31/history-of-peru-series-%E2%80%93-part-8-ancient-textiles/11565/

What trendy metrosexual would not be happy to sport this Wari-inspired tapestry in their post-modern apartment overlooking the Thames, the Seine, the Hudson, Niteroi Bay in Rio de Janeiro, the sea in Chorrillos, or wherever.

Somewhat pre-Picasso, the Wari people and empire (Peru AD 600 to 900) were “abstract artists” abstracting barely recognizable yet iconic images from their cultural repertoire. Their art now informs directly the output –for example—of Or Tapestries (left), as it did the artists and architects of the Bauhaus school and hence the development of modernist architecture, and even – who knows – the design of our metrosexual’s flat.

THE RICH HERITAGE OF TEXTILE DESIGN

The following chronology may help us to understand the rich background of “source inspiration” that Peruvian artists – and those producing master-pieces (as above) and journeyman-pieces (both unhelpfully subsumed in Peru into the category of “artesania” or handicrafts) – are able to draw on.

The way archaeologists, particularly, divide up the Peruvian past is complicated. So don’t try to do this for all of what is Peru today! There has been understandably a tendency to collect together all ancient cultures under one heading “Peru” – not least in order to provide a strong unifying heritage which strengthens a sense of identity. Once we become less obsessed with linking everything in with the history of the contemporary nation-state life become a little easier.

First, the two main (most enduring, on present evidence) threads, if you’ll excuse the pun, of textile development in Peru. (Every year we seem to have new archaeological evidence that adds threads and stitches to this complex tapestry – the story of Peruvian textiles):

1. The “North” radiating from the Chavin-Trujillo (Moche and Chimu) axis – with imperial “interruptions” from the Huari (250 years), from the Incas (80 years) and from Spain (300 years).

2. The “South” radiating from Paracas, Nasca, Ayacucho and Cusco.

This seems to point to a “center” (if there is one) which coincides with the “first cities” 200 kilometers to the north of Lima – but let’s start with the north, focusing on the area around what today is Trujillo.

The North

The oldest textiles – Chavin period (1000 to 100 BC)

In textiles Peru has another first! The longest continuous textile record in world history. Plant fiber basketry survives from about 10,000 BC and weavings made on a loom are still with us from the Chavin period (1000 to 100 BC). OK – the sample on the right is a bit faded and the worse for wear but this somewhat terrifying proclamation of God as nature (perhaps!) dates from about the same era as classical ancient Greece. How many shirts or blouses do you have left from even ten years ago? So stand in awe when viewing this. Lima’s own masterpiece of architecture from the Chavin era is the disgracefully neglected Garagay in the suburb of San Martin de Porres. In this drier coastal zone textiles should be better preserved but few or none remain (from Garagay). Perhaps the Lima area sent all its most precious art to Sotheby’s before the archaeologists could get at it! Via the huaquero, of course.

There is a fairly straight run of cultures – Chavin, Moche, Wari, Chimu, Inca – in what we are calling the North and ‘by their works ye shall know them.’ The Moche emerged somewhat after the Chavin influence declined and although better known for their ceramics, produced impressive textiles. Moche art is known for its realism whereas the culture which followed, called Wari, produced stunning abstract or stylized designs.

For the Moche or Mochica people the Wari culture was an import or invasion from the south and the evidence of its influence in the north is fragmentary and perhaps not of great duration (less than the 300 years suggested by the chart). During the Wari period abstract design developed further and centuries later (that is, by the 1920’s) came to influence the Bauhaus-based modernist movement of artists and architects in Germany.

By about 1100 the Chimu were constructing a vast urban complex at Chan Chan – a few kilometers in the direction of the coast from a previous power centre: the giant Moche terraced platforms which we call the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon – just across the Moche River from Trujillo. Chimu design in textiles seems to reinstate anthropomorphic patterns at the expense of the abstract and develops semi-sculptured textiles. The Wari and the Chimu both take urban design a stage further (recognizably modern towns) and the Wari predate the Inca in developing a road system, quipu communications, etc.

Diversion

The Peruvian Times impromptu prize for the best exhibit goes to the Museum fuer Weltkultur in Frankfurt for the stitched feather poncho (see left) in its collection. It is extremely rare and in exceptional condition. In detail, seen close-up it is even more magnificent. The Museum’s system of providing you with a featherweight “Kunstlerstuhl” (artist’s chair), and laminates to read on each exhibit as you sit reasonably comfortably, ought to be copied in every museum. For many people standing-and-looking-at-museum-exhibits fatigue kicks in after 100 meters or so. Not so at the Weltkultur in Frankfurt.

The South

The artistic predecessors of the Wari , an Andean people from Ayacucho, were the Nasca or Nazca and before them the Paracas cultures.

The Paracas culture produced some of the most “dazzling” textiles the world has seen. The Director of the British Museum, in selecting 100 objects to tell the history of the world, chose a fragment of a Paracas textile. “These textile fragments are made of alpaca or llama wool and would originally have been part of a cloak. They depict flying shamans grasping human heads in their talons. The bottom figure carries a knife used to behead his victim. They were found wrapped around mummified bodies in the great Paracas Necropolis in Peru. These 2000-year-old textiles were preserved in the dry, dark conditions of the tomb.” The fragment shown is dated about 300 BC.

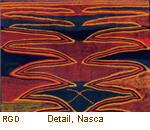

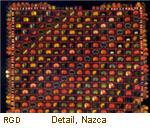

The Nasca period (100 – 700)

Possibly 500 years later than the fragment above, the textile border (far right, 87.25 x 6 inches), made of camelid wool and natural dyes, comes from the Nasca culture, south coast of Peru. The other two textiles are a a stark change towards abstract or geometrical designs. This is sometimes seen as part of a process – “the Nasca-ization of the sierra” – which in all probability included the spread of the Aymara language throughout the later Wari Empire, laying the basis for its present domination in Bolivia.

The Wari period (AD 600 – 900)

How many yarns to the inch? This sounds a bit like an Irish comedian’s start-up routine. The Wari produced some of the most finely-woven textiles in the world, with almost 200 yarns to the inch. It’s reckoned that if you unraveled a Wari full-size weaving – a tunic, say – the thread would reach to almost ten miles: enough to link Lima with Callao and to keep an Ichma slave in work for several months.

It has been noted in earlier parts of this series that specialized net-making for coastal fishermen spurred on the formation of America’s first towns and cities. The complexity of Wari weavings suggests specialized workforces, urban societies, and working under the patronage of the state or religious establishment. It would be several centuries before textile production in Peru received the same amount of artistic and administrative attention. Was it downhill all the way for textiles after the Wari? Well, not quite. Pop round to the Amano private museum (make an appointment first and tell them that in your opinion Chancay is tops and you will be welcomed with a smile and an abrazo) and see for yourself .

The period of regional excellence (AD 900 – 1200)

Somehow wedged between the empires of the Wari and the Incas several cultures with names perhaps not so well known confuse our desire for a simple chronology: Lima-Ischma, Chancay, Warpa, Chanka, etc – unlike the North, where the Chimu gave us one simple life-saving label to hang onto in this sea of differentiated cultures. In the field of textiles, Chancay is perhaps better known to Limeños. The Amano Museum holds an unrivalled collection.

Both the North and the South traditions were cut abruptly short by the rapid expansion of the Inca state 1200 – 1570 (at the outside – if you include Vilcabamba).

In Lima the Inca had a presence from about 1478 to 1533. They also, standing on the shoulders of their precursors, produced fine weavings.

Confession: I am, like many who enter the subject, bowled over by Peruvian textiles, so I may have been too overenthusiastic at times.

I rest my case this week, not on multiple references, but simply on the textiles themselves or the fine reproductions of them in the not-mainly-for-the-coffee-table book Textiles of Ancient Peru, published by Robert Gheller Doig (RGD) and from which many of the illustrations in this article are taken, with permission.