Papyri reveals workers received medical treatment and paid sick leave 3,600 years ago

Victoria Woollaston

Source- http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2955864/Ancient-Egyptians-NHS-Papyri-reveals-workers-received-medical-treatment-paid-sick-leave-3-600-years-ago.html#ixzz3RvmJ5znH

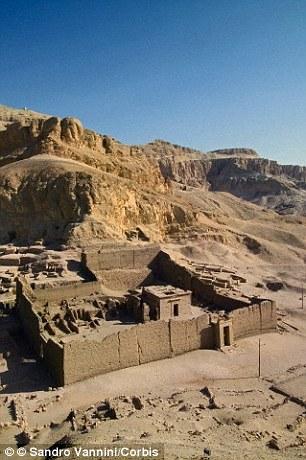

Ancient texts uncovered in Egyptian village Deir el-Medina (Ptolemaic temple pictured) suggest New Kingdom workers had state-supported health care

Many of us consider national health services as relatively new innovations of the 20th century, but they appear to have much older origins. Ancient texts uncovered among the human remains of an Egyptian village suggest workers from the New Kingdom had their own version of a state-supported health care. This scheme, which involved paid sick leave and on-site doctors, made sure workers making the king’s tomb 3,600 years ago were productive and well looked after.

The dig of the ancient Egyptian worker’s village at Deir el-Medina is being led by Stanford archaeologist Anne Austin. The village was built for workmen who made the royal tombs during the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 BC). During this period, kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in a series of rock-cut tombs.

The village was purposely built close enough to the royal tomb to make sure the workers could hike there on a weekly basis.

‘These workmen were not what we normally picture when we think about the men who built and decorated ancient Egyptian royal tombs - they were highly skilled craftsmen,’ said Dr Austin. ‘The workmen at Deir el-Medina were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.’

According to ancient texts found on the site, as well as other historical accounts, the Egyptian state paid workers monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to help with laundry, grinding grain and porting water. The worker’s families lived with them in the village, and their wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state.

Among these texts are also numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occurred when a workman was too sick to work, for example.

Ancient texts found among human remains (pictured with lead archaeologist Anne Austin) include daily records detailing when and why workers were sick and reveal they were also paid a certain amount of sick leave. Other papyri describe on-site physicians who would treat the workers as part of their employment

Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina were consistent enough to suggest these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days, explained Dr Austin. ‘These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician,' she continued. ‘The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. ‘The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina.’ This physician would have most likely treated the workmen with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus.

These texts acted like a reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for different ailments.

The longest of these ever found is called Papyrus Ebers and contains more than 800 treatments covering eye problems to digestive disorders. The source of the papyrus is unknown, but it was said to have been found between the legs of a mummy in the Theban necropolis. A suggested treatment for a condition that had symptoms similar to asthma is listed as a mixture of herbs heated on a brick so the sufferer could inhale the fumes. Another treatment, this time for intestinal worms, required the physician to cook the cores of dates and a desert plant called colocynth together in sweet beer.

‘These workmen were highly skilled craftsmen,’ said Dr Austin. ‘[They] were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.’ Wooden Egyptian tools are pictured

He would then have sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days.

Some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in the texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.

Egyptologist Dr Anne Austin (pictured) also said she found evidence of both health care and significant occupational stress in human bones recovered from the site. According to ancient texts the Egyptian state paid workers monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants

Despite paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician, it is clear that in some cases the workmen were working through their illnesses. For example in one text, a workman called Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. Dr Austin said: ‘The text tells us he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. ‘He then hiked back to the village of Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next ten days until he was able to work again. ‘Though short, these hikes were steep [and] Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys were likely at the expense of his own health.’

Dr Austin said this suggests sick days and medical care were not ‘magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state’, but were calculated provisions designed to make sure the workers were as productive as possible.

ANCIENT MEDICAL TREATMENTS

The longest medical papyrus ever found is the Papyrus Ebers (pictured). It contains more than 800 treatments for eye problems to digestive disorders

Texts found on the site of Deir el-Medina identify a workman on the crew designated as the 'swnw', or physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. This physician would have most likely treated the workmen with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus.

These texts acted like a reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for different ailments.

The longest of these ever found is called Papyrus Ebers and contains more than 800 treatments covering eye problems to digestive disorders. The source of the papyrus is unknown, but it was said to have been found between the legs of a mummy in the Theban necropolis. A suggested treatment for a condition that had symptoms similar to asthma is listed as a mixture of herbs heated on a brick so the sufferer could inhale the fumes. Another treatment, this time for intestinal worms, required the physician to cook the cores of dates and a desert plant called colocynth together in sweet beer. He would then have sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days. While smearing a paste of dates, acacia, and honey to wool and applying it as a pessary would be used as a form of contraception by the worker's wives.