A case study in hydraulic technology

Noah Wiener

Source - http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/daily-life-and-practice/delikkemer-hydrating-democracy-at-patara/

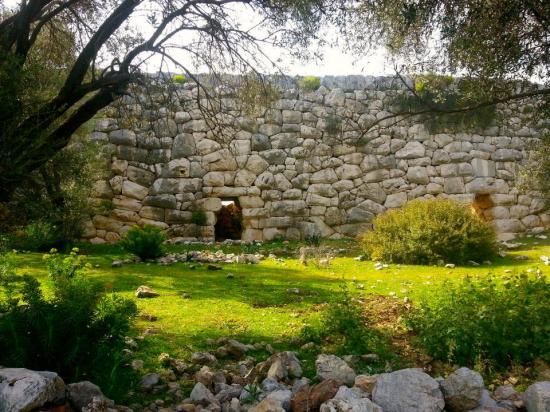

The inverted siphon at Delikkemer, near the ancient city of Patara.

When most of us think about the ancient world, we picture antiquity’s grandest monuments, enterprising monarchs and deadliest conflicts. But before the iconic wonders of the ancient world could be built, sufficient infrastructure was needed to support a population. The most important resource is water, and access could be a challenge in the often-arid Middle East and Mediterranean. The ancient engineering feats employed to supply fresh water differed from city to city, and often they were nothing short of miraculous.

BAR readers know about antiquity’s famous water systems such as Jerusalem’s tunnels, Rome’s aqueducts and Constantinople’s cisterns. But what about those of smaller cities, which were often built on strategic routes without freshwater access? As a case study, let’s take a look at ancient Patara, on the southern coast of Turkey. Never heard of it? This often-overlooked city played a vital role in the development of western political thought as well as early Christianity. The hometown of St. Nicholas (Santa Claus), Patara was the capital of Roman Lycia, the birthplace of federalist democracy. The French enlightenment thinker Montesquieu, whose theory of separation of powers greatly influenced the American Constitution, described the Lycian government at Patara: The Lycian republic was an association of twenty-three towns; the large ones had three votes in the common council, the middling ones two, and the small towns one… In Lycia the judges and town magistrates were elected by the common council, according to the proportion already mentioned… Were I to give a model of an excellent confederate republic, I should pitch upon that of Lycia.

The recently restored parliament building at Patara.

However, the port city of Patara did not have sufficient freshwater supplies to support this pioneering democracy. In the Roman era, the city was supplied by fresh mountain water that flowed through nearly fourteen miles of aqueducts. While the engineering behind aqueducts is often quite complex, the principle is simple: Water flows along a channel that steadily descends from its source to its destination. But what happens when that water needs to cross a valley? Ancient engineers lost their most important ally: gravity.

Lycian Way hiker Limor Finkel crosses underneath the wall supporting Delikkemer’s inverted siphon.

Roman engineers often tackled this problem using monumental bridges to keep the water at a steady elevation, and the Patara aqueduct system includes several of these. But sometimes, the topography of the land makes bridges impossible, forcing the engineers to think of a new plan. One such innovation is called an inverted siphon, such as the one at Delikkemer near Patara.

An inverted siphon is a pressurized water conduit. One end sits at a higher elevation than the other, and the center is the lowest point. The Delikkemer siphon, which was renovated following an earthquake in the first century C.E., is built out of stone blocks laid across the top of an impressive several-hundred-foot-long wall. Foot-wide piping holes were carved out of the blocks, which were fitted into each other and sealed for water-tight flow. Because the system was closed off and pressurized, when water flowed into the higher end, it was forced through the system across the valley. This so-called inverted siphon allowed the aqueduct to cross lower elevations, forcing the flow against gravity at certain points.

This stone pipe could be cleaned or replaced as it carried water through Delikkemer en route to Patara.

The engineers behind the Delikkemer system kept proper maintenance in mind. Kate Clow, the explorer behind Turkey’s popular Lycian Way hiking trail, described the blocks in the Turkish paper Hurriyet Daily News:

The system was designed for easy maintenance! If you examine the fallen blocks, you will find occasional ones with top-holes bored into them. These were for cleaning out deposits, and must have been sealed with a plug when the pipe was filled with water. There were also occasional stones where the socket cutout was extended so that a stone could be slipped out of the pipeline. Without this provision, to replace a faulty stone would have been impossible, as the blocks interlock completely. The pipe joints have traces of a lime cement used initially to seal them. However, the whole pipe is now thickly lined with a deposit of pink lime from the water inside it, and this must have quickly sealed any remaining leaks between the stones.

Ancient wonders were not only the domain of kings or priests; sometimes the most fundamental needs required the most impressive innovations.