PART.2

Ormaig, Argyll

The spectacular prehistoric cup-and-ring markings at Ormaig in Argyll have been recorded by high resolution sub-millimetre terrestrial laser scanning in 2007 and in 2014.

“This pioneering programme will allow stone weathering and erosion to be accurately monitored over time,” explains Ritchie.

“In this detailed hill-shaded surface model, two of the main ‘rosette’ motifs are shown using a combination of real colour texture - recording lichen growth - and greyscale depiction, allowing accurate measurement.

“The larger motif is perhaps the size of a dinner plate.”

Kraiknish Dun

This unusual late prehistoric dun sits on a prominent coastal rocky boss at the mouth of Loch Eynort on Skye.

Low altitude vertical and oblique aerial photos were taken with a remote controlled microcopter as part of a detailed archaeological investigation.

The dun is rougly triangular on plan with a level interious, and the massive drystone wall only survives around the landward-facing part.

An unusual outer wall is visible below the dun, with an inwardly curving entrance passage choked with rubble.

An orthographic plan used colour to depict changes in height at the important site.

“These extracts from the low altitude aerial photography and terrestrial laser scan surveys help illustrate the difficulty in seeing the walls remaining within the rubble.

“The site is situated on a rocky boss on the coast – a truly spectacular location.”

Achlain Bridges

General George Wade began constructing the military road network in the highlands between 1725 and 1733, building more than 400 kilometres of roads and around 40 bridges to link the barracks of Fort William, Fort Augustus, Inverness and Ruthven.

Major William Caulfeild expanded the network between 1740 and 1767 – an achievement Thomas Pennant credited with allowing the Scottish soldiery to breach rocks “supposed to be unconquerable”.

Once used by troops, supply carts and artillery, the three small bridges on the national forest estate in Glen Moriston are part of a surviving section of road which is now a scheduled monument.

Laser scan surveys informed a plan to record archaeological deposits and structural features during conservation work.

Lime mortar was used to consolidate the humped-back bridges. Steel frames, timbers and sandbags were also used in a project which concluded with a celebratory patrol by a small company of redcoats.

“The bridges should now stand for another 250 years,” reckons Ritchie.

St Bride’s Church

According to the Revered Francis Adam – the site’s last minister, who wrote a report at the end of the 18th century – this Aberdeenshire church and churchyard was built in 1637 and roofed with heather.

The roll of ministers, though, stretches back to 1567, and it was depicted as unroofed on the Ordnance Survey First Edition map of 1869.

The walls have largely been reduced to their footings, although the east gable survives. The building is described as “ruinous and collapsing”.

Exterior and interior elevations of the south wall depicted several construction phases and features, including a displaced headstone with the mortal emblems of an hourglass, skull and coffin, inscribed “...tear...wel liked...of Immanuel...Meek...this life...May M Kean 1696”.

Rectified photography allowed 45 individual gravestones to be examined, with a man and a woman, both of whom died aged 63, in 1722 and 1765, honoured with stones.

“The historic churchyard survey included a measured topographic survey alongside a photographic record and memorial transcription of the 18th and 19th century gravestones,” says Ritchie.

“Both surveys have enhanced the regional and national historic environment records and will inform conservation management.”

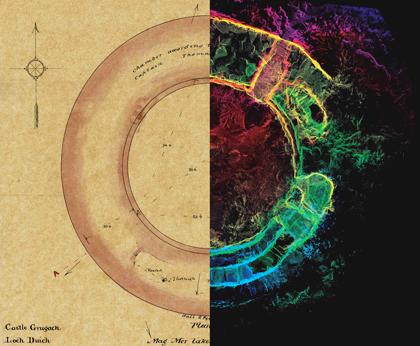

Caisteal Grugaig

This Iron Age broch has a huge triangular lintel over a low entrance passage and a well-preserved scarcement within a court which would have supported an upper floor, as well as chambers, stairways and passages within a thick, circular drystone wall.

Sir Henry Dryden made several “very attractive” (yet unpublished) drawings of the site in 1871 and 1872.

The broch was also recorded in a written description in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries for 1948-49.

A door check, barhole and guard chamber can be seen through elevation and laser scanning techniques, with those original descriptions proving as informative as the latest scanning techniques.

“The broch of Caisteal Grugaig overlooks Loch Alsh on the steep slopes of Faire-an-Dun – the ‘watching place’ of the tower,” says Ritchie.

“Few archaeological sites have such an illustrious history.

“This image contrasts the antiquarian plan drawn by Sir Henry Dryden in the 1870s with the modern terrestrial laser scan, colored by elevation.”