Ben Miller / Photos :© Forestry Commission Scotland

Source - http://www.culture24.org.uk//history-and-heritage/archaeology/art486536?

As an exhibition on some of the incredible finds in Scotland's national forests opens, Forestry Commission Archaeologist Matthew Richie reveals some of the survey secrets behind the discoveries

Torwood Broch

These ruinous drystone towers were built in the later first millennium BC and the first millennium AD on the Atlantic coast of Scotland, the Highlands and the Northern Isles.

They display “startling” architectural complexity, rising high from solid footings by employing a series of weight-saving and load-bearing galleries, stairways and passages within their double-skinned walls.

There are a small number of very unusual outliers in the Scottish lowlands and borders, constructed by specialists from the north working for a local tribal chief.

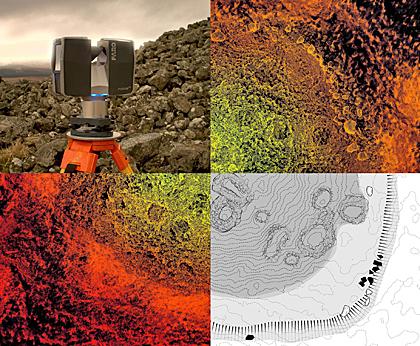

This broch, at Falkirk, was laser scanned in a joint project between community groups, conservation bodies and government agencies.

A photographic panorama revealed stonework, scarcement, recesses, lintels and an entrance passage, among other features.

“Brochs are truly unique to Scotland,” says Ritchie.

“They are impressive Iron Age drystone towers – perhaps 20 metres across and around nine metres high.”

Bucharn Cairn

With wide views over the Water of Feugh in Aberdeenshire, this round cairn is an imposing, largely undisturbed 3,500-year-old monument, made up of a mass of stone thought to cover a central stone cist and burial.

A hill-shaded terrain model helped to interpret its form and shape. The foundation is likely to have been an original feature rather than simply an apron of later field clearance.

“The massive Bronze Age burial cairn at Bucharn is about 30 metres in diameter and stands five metres in height,” says Ritchie.

“It is at least 3,000 years old. It retains the original domed profile because it was built on an unusual foundation platform, identified during the modern laser scan.

“This image captures the profile of the cairn at sunset and in the pointcloud created during the survey.”

Castle O’er

Several phases of occupation are revealed in the White Esk Valley.

The later inner enclosure was built within and upon an earlier series of ramparts, while there are traces of roundhouses dating from the early centuries of the 1st millennium AD.

Several satellite forts, enclosures, ring grooves and intercutting timber footprints evidence the scale of the occupation.

“The impressive Iron Age hillfort in the Scottish Borders has been recorded by low altitude aerial photography, using a remote controlled microcopter,” says Ritchie.

“It is presented as a traditional archaeological plan, showing details like the roundhouse foundation grooves in the interior, draped over a hillshaded contour terrain model giving it a great 3D perspective.

“The terrain model was surveyed by taking thousands of individual measurements.”

Wallace’s House

The promontory fort of Wallace’s House, in Dumfriesshire, had not been surveyed since the Ordnance Survey first edition map in 1857.

“It is defined by a massive ditch and rampart and is set above the confluence of two burns,” observes Ritchie.

“The original Ordnance Survey first edition map has been draped over a modern hill shaded terrain model – the perfect blend of old and new.

“It helps illustrate the impressive defensive position and retains the original attractive OS survey from over 150 years previously.”

PART.2