Earliest evidence of olive oil production and use – possibly in whole world, say excavators.

Ruth Schuster

Source - http://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/.premium-1.632310

Clay vessel containing olive oil dated to about 8,000 years ago at Ein Zippori. Photo: Israel Antiquities Authorityy

Remains of olive oil some 8,000 years old have been identified in pottery sherds found at Ein Zippori, in a massive Early Chalcolithic site discovered serendipitously when widening a road.

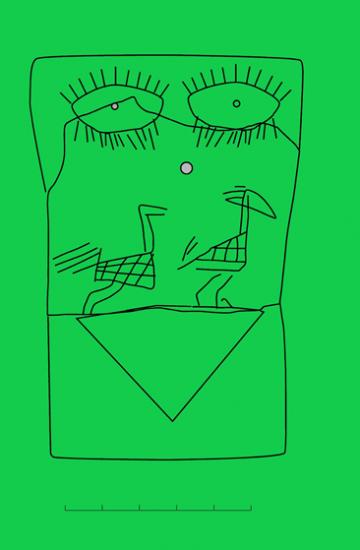

Aside from the earliest known actual remains of olive oil, as opposed to indirect evidence of olive oil production, the site also features domestic buildings and multiple cultic areas with stunning finds, including animal bones and stone palettes (typically about 10x10 centimeters in size) carved with two-dimensional animal motifs.

Reconstruction of the cultic stone palette with images of animals and eyes, by Nimrod Getzov. Photo: Israel Antiquities Authority

Digging from 2011 to 2013, the archaeologists also found pottery vessels, a great deal of flint items – notably sickle blades and axes and even fine stone vessels, such as bowls. And, clay vessels that proved to have olive oil inside.

A clay vessel with olive oil residue found inside, from 8,000 years ago. Photo: Israel Antiquities Authority

Ein Zippori is some 2 kilometers from the ancient town of Zippori, but is millennia older: there is no connection between it and the "classic" site of city. It is also situated right by Highway 79, a very busy traffic artery, which is why the road needs expansion – which in turn is how the site was found, explains Dr. Ianir Milevski of the Israel Antiquities Authority, who dug there in 2011-2013 together with Nimrod Getzov.

Naturally we can't know what the place was called then, but the site at Ein Zippori had clearly been occupied by a very large settlement – about 40 dunams or 4 hectares - over multiple periods in antiquity, Milevski says.

When the pottery storage vessels were first found, naturally the scientists couldn't know what had once been inside – olive oil, wheat, wine or something else. Analysis requires sending pieces of the vessels, which they must be careful not to contaminate for instance by touching, to the lab, which could test the organic remains that had been absorbed by the clay of the vessels. This Milevski and Getzov did; and the sherds were tested by Dr. Dvory Namdar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

"We took several samples, not only from the Early Chalcolithic but other periods as well," says Milevski. The result was unambiguous: the vessels had been used to store olive oil.

What species of olive cannot be known; archaeologists have sharply differing opinions about that, let alone when the olive became known and used in the Levant. Comparing the ancient extracts with modern 1-year old oil shows a strong resemblance, the IAA says. But the find proves that olive oil existed and was being produced 8,000 years ago, Milevski tells Haaretz.

In other words, it shows that 8,000 years ago, the civilization of the Levant had reached the second stage of domesticating plant life. The first stage was the domestication of lentils and grain, which began about 10,000 years ago. Trees such as the olive were the second stage.

The find cannot infer that the people then had achieved domestication of the olive, he qualifies – just that they knew what to do with it.

A previous find by Dr. Ehud Galili and other, of thousands of crushed olive pits found at Kfar Samir, a prehistoric settlement off the Carmel coast south of Haifa, dating to about 6,500 years ago. That's some three hundred years later than the Ein Zippori find, Milevski clarifies. Since there is no knowing why people who lived so long ago were crushing olive pits, we cannot categorically say they were making olive oil, he points out; no oil was actually found. "We found the oil," he adds. No older findings of actual oil have been announced anywhere else.

Their findings were published in the Israel Journal of Plant Sciences.

A clay vessel with olive oil residue found inside, from 8,000 years ago. Photo: Israel Antiquities Authority