Hannah Osborne

Source - http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/ancient-bolivian-mortuary-where-corpses-were-stripped-flesh-uncovered-andes-foothills-1489146?

The stone mortuary was used for about 400 years, experts say.(Antiquity Publications Ltd 2015)

An ancient mortuary where corpses were stripped of their flesh so their families could take them with them on their travels has been uncovered by archaeologists in Bolivia.

The mortuary was found in the foothills of the Andes by researchers at the Franklin & Marshall College in Pennsylvania.

Published in the journal Antiquity, From Bodies To Bones: Death And Mobility In The Lake Titicaca Basin, Bolivia, is a study that looks at how a society dating back between 2,200 and 1,500 years ago disposed of their dead.

Scott C Smith and his team found a circular building where the floor was covered in 1,000 teeth and small bones – a room where human body parts were taken to be boiled, stripped of their flesh and cleaned.

"Disposal of the dead in early societies frequently involved multiple stages of ritual and processing," the authors wrote. "At Khonkho Wankane in the Andes, quicklime was used to reduce corpses to bones in a special circular structure at the centre of the site."

According to USA Today, when the quicklime was mixed with water, it was able to remove tissue and fat from bones. Exposure to air would then have turned the mixture into a white plaster – inside the mortuary, the researchers found body parts coated in this substance.

The quicklime was applied to the body parts. Larger bones were then removed from the site, suggesting the dead were taken away by their families to be buried somewhere else.

"Khonkho Wankane was a ritual centre to which the dead were brought for processing and then removed for final burial elsewhere," the authors wrote.

The excavation was part of a larger multinational and collaborative project.The site of Khonkho Wankane is located near the southern shores of Lake Titicaca. It predates both the Inca and Tiwanaku civilisations and is from a period of time known as the Late Formative – between 200BCE and 500. At the time, Khonkho Wankane was one of a network of religious and political centres in the area.

Smith told IBTimes UK they were surprised to find so many bones as they had assumed the site would be primarily residential: "We did not expect to encounter this highly specialised structure dedicated to mortuary ritual."

Many ancient Andean communities placed the dead in high esteem, with them playing an active role in social life. It is thought the Inca would bring out past emperors for ceremonial occasions and consult them on political and religious maters. However, there is no other evidence to show these ancient communities cleaned and curated the bones in the manner described at the mortuary.

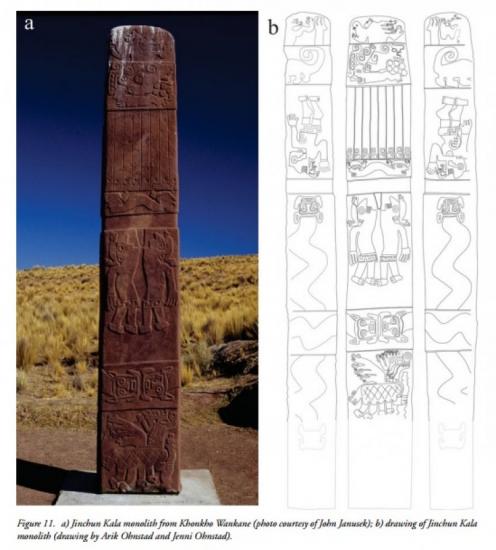

The monolith depicts someone with defleshed ribs.(Antiquity Publications Ltd 2015)

Researchers believe the mortuary was used for about 400 years. Outside, there was a carving on a stone pillar showing a human with defleshed ribs.

"The back and sides of the monolith seem to portray individuals in movement," they wrote. "Moreover, these individuals appear to move up the back of the monolith with flesh and down the sides partially defleshed, with the ribs portrayed as exposed.

"This may be a depiction of the process of producing bones that we have associated with [the structure]. Human remains enter Khonkho Wankane with flesh and leave as bone."

Smith said the dead were an important part of life for communities near Khonkho Wankane and people who stopped off at the mortuary were llama drovers who would not have been able to live close to burial sites. Instead of leaving them behind, they took their dead on the road with them, researchers believe.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, he said: "For many cultures in the Andes, the dead were active participants in the lives of the living. Dead ancestors were often preserved, sometimes through mummification, and then consulted on religious and political matters by the living.

"What is interesting about this case is that during this particular period of time in the Lake Titicaca basin people were quite mobile. Trade caravans connected far-flung regions such as the deserts of northern Chile and the warmer eastern valleys of the Andes.

"In a context characterized by mobile agropastoralists and caravan traders, how did the dead continue to play a role in the lives of the living? We think that this research begins to provide an answer to this question. We argue that ritual specialists at Khonkho Wankane performed a specialised function for mobile groups that visited the site. We think they transformed dead bodies into curated bones that could then be removed from the site as these mobile groups continued on their ways."

The authors conclude: "Whereas archaeologists typically have access to the final resting point of mortuary remains, the data from Khonkho Wankane give us a window into a midpoint of a spatially and temporally extended process of transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead."