Fall of Gaddafi’s regime allows archaeologists in to explore hidden ancient civilisation

Source - http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2060396/Fall-Gaddafi-s-regime-allows-archaeologists-explore-hidden-ancient-civilisation.html#ixzz1dQPxJfsY

- British team discovers 250,000sq mile kingdom in Libyan wastelands

- Found more than 100 castles and underground irrigation tunnels

- Ruled by 'highly civilised' black African people called the Garamantes

- Culture thrived for 600 years after birth of Christ in bleak landscape

- Lay forgotten after Gaddafi erased culture's history from curriculum

- Archaeologists preparing to probe site further after fall of dictator

British archaeologists are preparing to explore an ancient kingdom lost in the desert sands of war-torn Libya.

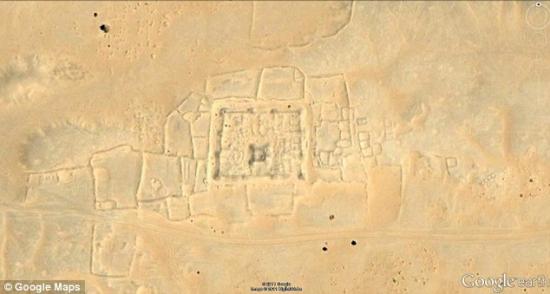

Satellite images have uncovered an advanced Saharan civilisation in south-western wastelands that experts believe will 're-write the history of the country'.

The 'highly civilised' kingdom was ruled by a north African people called the Garamantes, who imported luxury goods and thrived for 600 years until about 600AD.

Vast: The site of the ancient Garamantes civilisation stretches for 250,000sq miles across the south-western wastelands of Libya. The culture can finally be explored after the fall of Colonel Gaddafi

Lost in the sands of time: Little is known about these fascinating mud brick remains or the people who inhabited the area in the Middle Ages because their history was suppressed under Gaddafi's dictatorship

The fall of Gaddafi's regime has paved the way for archaeologists to explore the massive 250,000-square-mile site.

A team of explorers have already discovered over 100 qsurs (castles), fortified towns and villages, along with sophisticated underground irrigation channels.

Professor David Mattingly, an expert of Roman Archaeology at the University of Leicester, said: 'It is like someone coming to England and suddenly discovering all the medieval castles.

'These settlements had been unremarked and unrecorded under the Gaddafi regime.

'It is a new start for Libya's antiquities service and a chance for the Libyan people to engage with their own long-suppressed history.

'The Garamantes were highly civilised, living in large-scale fortified settlements, predominantly as oasis farmers.

'It was an organised state with towns and villages, a written language and state-of-the-art technologies.

'They were pioneers in establishing oases and opening up Trans-Saharan trade.'

Tantalising clues: The British archaeologists from Leicester University assess the ruins of the highly-skilled black African culture which thrived for 600 years in spite of the inhospitable environment

Advanced: The experts have already discovered more than 100 castles, known as qsurs, fortified towns and villages, and sophisticated underground irrigation channels, which the Garamantes used to extract around 30billion gallons of water

Libya's curriculum under Gaddafi ignored the history of this highly-skilled black African culture which existed before Islam.

But now the British archaeologists - who had to flee when civil war broke out - believe the dictator's death will allow Libyans to learn about their long-forgotten past.

During the Nato air strikes against Gaddafi, Professor Mattingly even supplied military chiefs with the co-ordinates of key archaeological sites in order protect them from bomb damage.

He added: 'These represent the first towns in Libya that weren't the colonial imposition of Mediterranean people such as the Greeks and Romans.

'The Garamantes should be central to what Libyan school children learn about their history and heritage.

'I would love to get back before the end of the year - this site is unbelievably special and I have many Libyan friends I have been concerned about.

'We will have to see how conditions progress over the coming weeks.'

Complex: A view of the remains of the ancient kingdom on Google Earth. The Garamantes were depicted by the Romans as barbaric, but they were the first civilisation in history to transform a major riverless desert into a complex urban society

Amazingly, the Garamantes - portrayed by the Romans as barbaric, troublemaking nomads - were the first civilisation in history to transform a major riverless desert into a complex urban society.

Their desert culture flourished by using underground water extraction tunnels - known as 'foggara' in the Berber language.

The construction of these tunnels was highly labour-intensive, requiring huge numbers of slaves.

It is estimated that the Garamantes extracted around 30billion gallons of water from their subterranean tunnels.

But the water started to run out in the 4th century, forcing them to dig deeper - as well as import more slaves than their military power could successfully deliver.

The archaeological team have already identified mud brick remains of castle-like complexes, with walls standing up to 4m high.

There are also traces of domestic dwellings, cemeteries, wells, fields, sophisticated irrigation systems and remnants of their own alphabet related to modern-day Touareg script.

Dr Martin Sterry, who was responsible for image analysis, said: 'Satellite imagery has given us the ability to cover a large region.

'The evidence suggests that the climate has not changed over the years and we can see that this inhospitable landscape with zero rainfall was once very densely built up and cultivated.

'These are quite exceptional ancient landscapes, both in terms of the range of features and the quality of preservation.

'It was an organised state with towns and villages, a written language and state-of-the-art technologies.'

The Libyan antiquities department, badly under-resourced by Gaddafi, is closely involved with the project.

The team has also received funding from the Leverhulme Trust, the Society for Libyan Studies, the GeoEye Foundation and £2.5m from the European Research Council.