Noah Wiener

Source - http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-israel/early-bronze-age-megiddos-great-temple-and-the-birth-of-urban-culture-in-the-levant/

The Early Bronze Age (EBA, 3,500-2,200 B.C.E.) produced the world’s first urban and literate societies, and by the end of the era, EBA society bore witness to the construction of the pyramids at Giza and the birth of the Akkadian Empire. In the first centuries of the Bronze Age (Early Bronze Age I [EB I], ca. 3,500-3,000 B.C.E.), Mesopotamian Uruk flourished into a monumental city, sparking what Gordon Childe controversially termed an “urban revolution” in Mesopotamia.

Things were different in the southern Levant. Scholars traditionally depict the EB I Levant as a village-level society, with cities first appearing in the early third millennium B.C.E. (Early Bronze Age II and III). However, monumental finds at Megiddo may change that picture.

Excavations in Megiddo Area J uncovered a temple of unparalleled scale in the Early Bronze Age I Levant. This photo from the 2008 field season is courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition.

Recent excavations in and around Early Bronze Age I Megiddo have exposed a complex society, “settlement explosion” and monumental construction that are unparalleled elsewhere in the late-fourth millennium Levant. At the center of these discoveries lies Megiddo’s Great Temple, a structure that,according to its excavators, “has proven to be the most monumental single edifice so far uncovered in the EB I Levant and ranks among the largest structures of its time in the Near East.”

Two recent articles in the American Journal of Archaeology and Near Eastern Archaeology explore not only the excavation of the Great Temple and its construction, but also the occupation of greater Early Bronze Age I Megiddo, a “dual site consisting of a cultic acropolis at Tel Megiddo and the settlement at Tel Megiddo East.”

Who built the Great Temple? And what does their settlement size and complex labor organization suggest about the Early Bronze Age I Levant? In personal correspondence with Bible History Daily, Megiddo archaeologist and W.F. Albright Institute Dorot Director Matthew J. Adams describes EB I Megiddo:

The society of the Great Temple builders is still something of a mystery. We used to think that EB I society in general was not complex enough for political and social hierarchies, but the Great Temple and the settlement at Tel Megiddo East are changing that. At both sites, substantial activity and construction suggest a prosperous mid-to-late EB Ib society, culminating in the Great Temple phase, which featured monumental architecture, standardization of measurements in public and private buildings both on the acropolis and in the settlement and planning over broad spaces. All of these things are characteristic of complex political and social structures.

Megiddo at a Glance

Before examining the Early Bronze Age Great Temple, let’s take a look the site’s broader history. Megiddo played a central role in the region’s history for millennia, both before and after its Early Bronze Age occupation. Over a century of investigations at the storied site of Megiddo have uncovered evidence of a thriving city that has been described as “the jewel in the crown of Biblical archaeology.” Timothy P. Harrison’s 2003 BAR article “The Battleground” included the following sidebar summarizing the extended history of Megiddo:

Strategically located on the important Via Maris trade route, ancient Megiddo (Tell el-Mutesellim) was designated “Armageddon” in the Book of Revelation, the site of the ultimate battle at the end of days. Megiddo was settled as early as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (8300–5500 B.C.E.). The Early Bronze Age I (3300–3000 B.C.E.) saw the creation of a large, unfortified settlement in an area to the east of the mound, which today rises 100 feet above the floor of the Jezreel Valley.

From the 20th century B.C.E. through the 12th century B.C.E., Megiddo flourished as a Canaanite city-state. In about 1479 B.C.E. it was conquered by Pharaoh Thuthmose III. Egyptian domination continued for over 300 years.

Canaanite Megiddo was destroyed by fire; the evidence of this destruction is assigned to Stratum VII (discussed by Timothy Harrison in the accompanying article). Somewhat later—the dating is still hotly disputed—the city represented by Stratum VI, which seems to have been of a mixed Israelite and Philistine character, also fell victim to fire. (A contorted skeleton and smashed pottery from this stratum testify to the violence of its end.)

Megiddo rose again in the ninth century B.C.E. as a lavish city, boasting an impressive gate, three palaces and puzzling structures often interpreted as stables. Following Tiglath-pileser III’s conquest of Megiddo in 732 B.C.E., the town became the capital of the Assyrian province Magiddu. By the fourth century B.C.E. Megiddo’s importance waned, and it ceased to be an important site.

The Great Temple of Megiddo

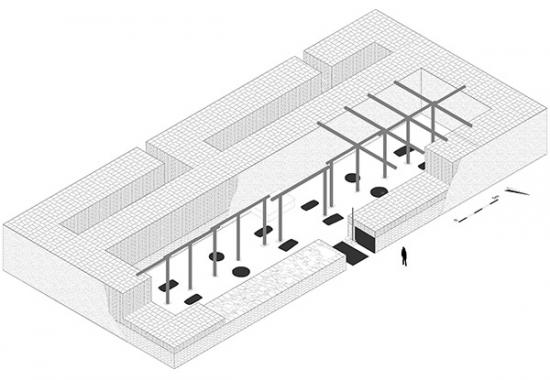

An isometric drawing of the Early Bronze Age I Great Temple at Megiddo. Illustration by (and courtesy of) Matthew J. Adams.

Two decades of renewed excavations at Megiddo have uncovered the unprecedentedly monumental cult complex described by Matthew J. Adams, Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin in “The Great Temple of Early Bronze I Megiddo” in the April 2014American Journal of Archaeology. The authors identify the Great Temple as a broad-room sanctuary (a vague Chalcolithic and EBA designation), or more specifically, a broad-room table temple, a type “defined by two elements: a broad room and central ground-level stone slabs at regular intervals within the room.” The temple, which replaced an earlier structure on the same site, was built according to a systematic geometric plan. Its thick mudbrick walls surround a main room featuring orderly planned sets of basalt tables and columns.

While we know of other Levantine broad-room sanctuaries, the AJA report reminds readers:

In considering the sophistication of the Great Temple and these aspects of its construction, it is useful also to reflect on the size of the building (1,100 m2) in comparison with that of contemporary and slightly later cultic structures. The Great Temple is roughly six times the size of the average broad-room table temple and similar in size to average temples in contemporary Mesopotamian cities. Ultimately, the Great Temple was one of the most sophisticated buildings of its day and required significant expenditures of ideological capital to rally the specialized and unspecialized labor necessary for its construction.

While cultic activity surely took place in the Early Bronze Age Great Temple, the monumental structure was cleaned and the sanctuary was uncovered devoid of cultic remains. So what was going on in the Great Temple at Megiddo? In correspondence with BAS, Adams noted that some questions remain unanswered:

Cult/religion in this period is still something we can’t describe very well. Some work has suggested that fertility cults associated with water and grain may have been the norm in the Early Bronze Age. Generally, in this model, EB religion is seen as similar to other types of Semitic religions attested in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, for example, at Ugarit. It’s hard to tell on the basis of present evidence if this is really applicable to the Megiddo temple.

The sheer size of the Great Temple provides clues about the complexity of the community’s structure. Construction of the Great Temple and Megiddo’s surrounding cultic precinct surely involved large-scale resource accumulation and labor organization. (For example, workers would have needed over a square mile of arable land just for straw used as temper in the Great Temple’s mudbricks.)

Complex administrative societies existed in contemporaneous Mesopotamia and Egypt, but Early Bronze Age I society in the Levant was not “globalized” like the later Bronze Age, and the Megiddo phenomenon should be evaluated primarily as a local development. What does this tell us about Early Bronze Age I Megiddo and the surrounding Jezreel Valley?

PART.2