Missing parts of sphinx found in German cave

Source -http://www.saudinewstoday.com/article/58312__Missing+parts+of+sphinx+found+in+German+cave

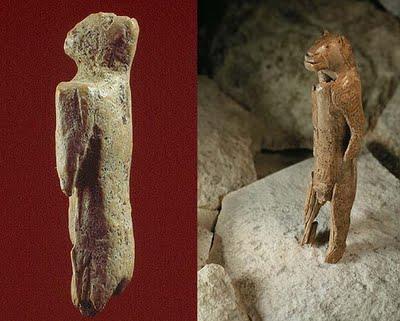

Archaeologists have discovered fragments of one of the world's oldest sculptures, a lion-faced figurine estimated at 32,000 years old, from the dirt floor of a cave in southern Germany.

The ivory figure, along with a tiny figurine known as the Venus of Hohle Fels, marks the foundation of human artistry. Both were created by a Stone Age European culture that historians call Aurignacian.

The Aurignacians appear to have been the first modern humans, with handicrafts, social customs and beliefs. They hunted reindeer, woolly rhinoceros, mammoths and other animals.

The Lion-Man sculpture, gradually re-assembled in workshops over decades after the fragments were discovered in 1939, is a kind of reverse sphinx: a human body, standing erect, but with the head of a now extinct European cave lion.

The head is finely cut, but there is not enough detail left in the body to judge whether this chimera was meant to be male or female.

Claus-Joachim Kind, the chief archaeologist at the palaeolithic site near the city of Ulm, said the figure, was probably used by a shamanistic religion.

"But we are walking on thin ice with any interpretation," he warned.

The fact that the figure was found without any tools close to it in the sediment does suggest that the site, the Stadel Cave, had a religious significance for its owners at the time.

Lion-Man is biggest Aurignacian item found in any of the caves at the site.

The span of time since the Aurignacian culture is immense.

The world's first cities, based on intensive, year-round agriculture, were established in Mesopotamia 7,000 years ago. The cave paintings of Lascaux in France, the world's best known Stone Age Art, probably date back 17,000 years.

But Aurignacian sites, including the caves in Germany as well as the Chauvet Cave decorated with murals in southern France, are twice as old, going back 32,000 to 40,000 years from the present, radio- carbon dating of the debris in the caves shows.

Several flutes found in the same sediment show that the Aurignacians also made music. Their pre-historical period is known as Upper Palaeolithic. The culture name comes from the first site to be studied, at Aurignac in the Haute Garonne area of France.

Over the past two years, German archaeologists have carefully excavated more of the sediment near the spot where the Lion-Man showed up. Thousands of bone fragments and some ivory pieces were found.

Some of them matched the Lion-Man perfectly, a delighted Kind reported.

"This a wonderful time," he said.

Some of the figure's missing right side and parts of the back have already been restored as a result.

"It needs a huge amount of patience," said Kind. "It's like doing a jigsaw puzzle in 3D."

The work is continuing with the help of computer tomograph images of the pieces and simulation software.

By next year, the Lion-Man may be complete.

The restorers have also concluded that Lion-Man was somewhat taller than the 30 centimetres of him that currently exist. He was carved from one tusk, with the artist forming the legs from two sides of tusk's hollow root.

The archaeologists assume that the Lion-Man is several thousand of years younger than the Venus, the Aurignacian female figure with an enormous bosom and hips which was found in a nearby cave, Hohle Fels, in 2008.

Though the dry caves were ideal to preserve them, both have turned brown with age.

The first fragments of Lion-Man were found in 1939 by Robert Wetzel in sediment, but not recognized until 30 years later.

The different caves are closed to the public and provincial authorities are considering applying to have them declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Some sediments inside, which have not yet yielded up their secrets, are being left untouched.

"We assume they still contain a large quantity of culturally important and unique artefacts," Kind said.

Replicas of the Lion-Man are on display in major museums in Tokyo, Paris and New York. The original is in the Ulm Museum. Dpa

Lion man from Hohle Fehls Cave [Credit: Hilde Jensen/Universität Tübingen/Thomas Stephan/Ulmer Museum]