Turkeys Part II: From bishop's novelty to family favourite

Mjs 76

In the second part of our epic exploration of turkeys, based on the PhD research of Brooklynne Fothergill, we look at how turkeys crossed the Atlantic – twice.

The first turkeys to reach Europe alive were a male and female sent by Alessandro Geraldini, Bishop of Hispanola, in 1520 to Cardinal Lorenzo Pucci in Rome with a note exhorting the recipient to admire them, but don’t eat them.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t long before turkeys became part of the European diet, spreading across most of the continent by the middle of the 16th century.

Turkeys were often given as gifts from one noble to another: they were large and impressive, they were different and exotic, and crucially, they could be adapted into existing recipes. (Whereas if you gave someone a coconut or a pineapple, their cook wouldn’t have a clue what to do with it.)

Bronze statute of a turkey by Giambologna, 1560 (image: Wikipedia)

The earliest known record of a turkey in England is a 1541 reference by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury. By 1612 they had even reached India.

The bird was viewed very differently on either side of the Atlantic. In the Americas it was your standard livestock but over in renaissance Europe, turkeys were – at least initially – the preserve of the wealthy and the privileged, sometimes kept in menageries to demonstrate status. A cooked turkey was an impressively sized lump of meat to display before important guests, especially when dressed up with the tail-fan. The alternative was the peacock which was harder to keep (certainly a lot noisier), harder to prepare and… look, with the best will in the world, it just doesn’t taste good.

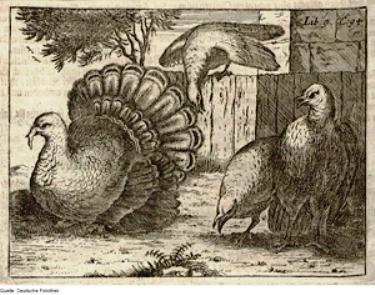

German woodcut by Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg, 1695 (image: Deutsche Fotothek/Wikipedia)

But turkeys didn’t stay the preserve of the privileged for long. Less than sixty years after that first pair arrived in Rome, turkey-breeding was big business. Huge turkey farms dotted the East Anglian landscape and each autumn hundreds of thousands of the birds were driven for weeks along country roads to London, their feet tarred and sanded for protection. You try doing that with chickens!

For all its ubiquity in America, and despite its advantages, the turkey was never going to replace the chicken as the de facto fowl of Europe. Instead it became associated with high days and holidays, great feasts and small. By Victorian times it was an established tradition for employers to give a turkey to their staff, as seen in A Christmas Carol where the reformed Scrooge sends the largest turkey in the shop to Bob Cratchitt, whose family were otherwise expecting to dine on goose.

“I cannot omit, however little it may seem, that this county of Suffolk is particularly famous for furnishing the City of London and all the counties round with turkeys, and that it is thought there are more turkeys bred in this county and the part of Norfolk that adjoins to it than in all the rest of England.”

Daniel Defoe, A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, 1726

Exactly one hundred years after the turkey first travelled eastwards across the Atlantic… it went back again. The New World colonists who sailed in the Mayflower thought along similar lines to returning Spanish sailors a century before: what has plenty of meat, doesn’t take up much room on board ship and is likely to survive a long sea-crossing? That would be turkeys: crate 'em up.

One can only imagine the mixture of delight and irritation experienced by the Pilgrim Fathers when they finally landed in Massachusetts and discovered thousands of the things wandering around…